NORTH AMERICA

Early formation

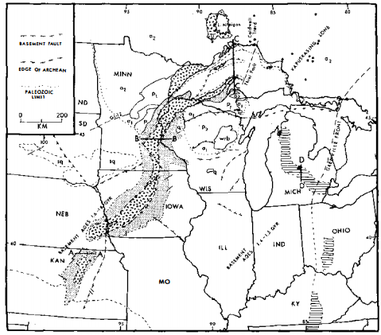

North America and Greenland first appeared in the Early and Middle Proterozoic as Laurentia, a patchwork of orogenic belts formed by collisions between Archean provinces and Early Proterozoic accretions (Hoffman, 1988). They subsequently underwent extensive crust creation and further orogenic activity (Wicander, 2004). Great quantities of juvenile crust were introduced by an incipient continental rift (1.1 Ga) (Davis, 1990) extending from central Michigan to central Kansas through Lake Superior (Van Schmus, 1985), as shown at right. The events of the Grenville orogeny (1.4-1.2 Ga) that deformed the eastern North American margin from Mexico to Labrador are thought to have been concluded by the collision of Laurentia with another yet unknown continent (possibly Amazonia) (Hanmer, 2000). Paleozoic North America, as part of supercontinent Pangaea, underwent six cycles of transgression and regression, each marking a cratonic sequence. The same era saw the growth of the Cordillera mountain belt along the western margin of North America, the Appalachians in the east, and the Ouachitas in the southeast (Wicander, 2004). (Van Schmus, 1985)

Mesozoic to Present

Transgression and regression continued as the fragmentation of Pangaea began in the Mesozoic. Today almost completely subducted beneath the North American plate, the Farallon plate caused four Mesozoic orogenies as it converged with western North America: the Sonoma, Nevadan, Laramide and Sevier (Wicander, 2004). Beginning with these orogenic events, over 100 terranes have been accreted to North America’s western margin (Wicander, 2004). During the Cenozoic, the Laramide orogeny formed the North American Cordillera from Mexico to Alaska, a mountain range characterized by various geologic features such as Basin and Range and the Rockies. (Wicander, 2004). The sediments deposited across the continental crust by transgression and regression cycles were scraped off the craton in large regions of Canada and northern United States by the recurrent formation and melting of Pleistocene glaciers (1.6 million years to 10,000 years ago) (Wicander, 2004).

Below, a video summarizes the formation of the North American plate from the present day to 550 million years ago.

North America and Greenland first appeared in the Early and Middle Proterozoic as Laurentia, a patchwork of orogenic belts formed by collisions between Archean provinces and Early Proterozoic accretions (Hoffman, 1988). They subsequently underwent extensive crust creation and further orogenic activity (Wicander, 2004). Great quantities of juvenile crust were introduced by an incipient continental rift (1.1 Ga) (Davis, 1990) extending from central Michigan to central Kansas through Lake Superior (Van Schmus, 1985), as shown at right. The events of the Grenville orogeny (1.4-1.2 Ga) that deformed the eastern North American margin from Mexico to Labrador are thought to have been concluded by the collision of Laurentia with another yet unknown continent (possibly Amazonia) (Hanmer, 2000). Paleozoic North America, as part of supercontinent Pangaea, underwent six cycles of transgression and regression, each marking a cratonic sequence. The same era saw the growth of the Cordillera mountain belt along the western margin of North America, the Appalachians in the east, and the Ouachitas in the southeast (Wicander, 2004). (Van Schmus, 1985)

Mesozoic to Present

Transgression and regression continued as the fragmentation of Pangaea began in the Mesozoic. Today almost completely subducted beneath the North American plate, the Farallon plate caused four Mesozoic orogenies as it converged with western North America: the Sonoma, Nevadan, Laramide and Sevier (Wicander, 2004). Beginning with these orogenic events, over 100 terranes have been accreted to North America’s western margin (Wicander, 2004). During the Cenozoic, the Laramide orogeny formed the North American Cordillera from Mexico to Alaska, a mountain range characterized by various geologic features such as Basin and Range and the Rockies. (Wicander, 2004). The sediments deposited across the continental crust by transgression and regression cycles were scraped off the craton in large regions of Canada and northern United States by the recurrent formation and melting of Pleistocene glaciers (1.6 million years to 10,000 years ago) (Wicander, 2004).

Below, a video summarizes the formation of the North American plate from the present day to 550 million years ago.

(The Hateful Dead, 2008)

SOUTH AMERICA

The South American Platform

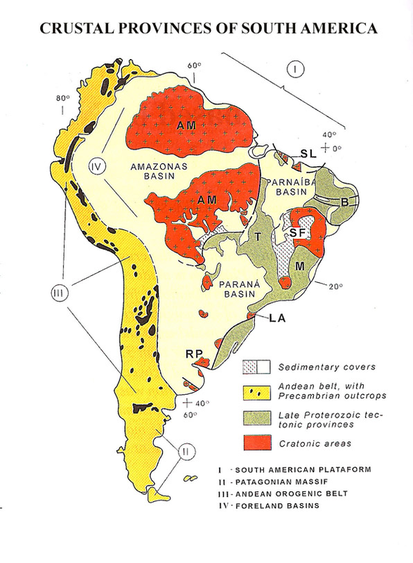

The South American Platform, the tectonically stable portion of South American continental crust (shown at left), was formed primarily by three cycles of orogenic activity: the Trans-Amazonian (2.2-1.8 Ga), the Late Mesoproterozoic (1.3-0.95 Ga), and the Brasiliano/Pan-African (0.9-0.5 Ga) (Almeida, 2000). The principal period of formation extended from 2.2 to 2.0 Ga (Early Proterozoic) during the Transamazonian orogenic cycle, although juvenile material from as early as 3.7 Ga has been found in the areas dating from 3.1 to 2.6 Ga (Archean) (Cordani, 1999). The Platform’s northwestern and southeastern formations are bound by the Transbrasiliano megasuture, a 3000-km crustal discontinuity marked by ridges and aligned drainage (Vidotti, 2011). The northwestern formation is characterized by the Amazonian and Sao Luis cratons, and the southeastern, by a group of small cratonic fragments the biggest of which is the Sao Francisco craton. Both these formations appear to have a shared history from 3.0 to 1.7 Ga, indicative of a common border throughout that period (Cordani, 1999). However, the Middle and Late Proterozoic saw the northwestern mass remain undamaged by tectonic and orogenic activity, while the southeastern formation was broken up (Cordani, 1999). By the beginning of the Brasiliano orogeny in the Late Proterozoic, 98% of the crust known to South America today had been formed (Cordani, 1999). The Brasiliano cycle brought the final changes to the structure of the South American Platform’s basement. The Platform was part of successive supercontinents until the early Phanerozoic, when it broke off from Western Gondwana (Almeida, 2000). The Brasiliano structures are the main source of sedimentary cover across South America (Almeida, 2000).

(Cordani, 1999)

The Andean Cordillera

Stretching 8000 km along the western coast of South America (yellow in the figure above), the Andean mountain range rose from the interactions of the Nazca plate with the South American plate. These interactions include convergence with oceanic terranes during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic (Northern Andes), subduction and volcanic arc activity (Central Andes), and the closing of a back-arc oceanic basin (Southern Andes) (Ramos, 1999).

The South American Platform, the tectonically stable portion of South American continental crust (shown at left), was formed primarily by three cycles of orogenic activity: the Trans-Amazonian (2.2-1.8 Ga), the Late Mesoproterozoic (1.3-0.95 Ga), and the Brasiliano/Pan-African (0.9-0.5 Ga) (Almeida, 2000). The principal period of formation extended from 2.2 to 2.0 Ga (Early Proterozoic) during the Transamazonian orogenic cycle, although juvenile material from as early as 3.7 Ga has been found in the areas dating from 3.1 to 2.6 Ga (Archean) (Cordani, 1999). The Platform’s northwestern and southeastern formations are bound by the Transbrasiliano megasuture, a 3000-km crustal discontinuity marked by ridges and aligned drainage (Vidotti, 2011). The northwestern formation is characterized by the Amazonian and Sao Luis cratons, and the southeastern, by a group of small cratonic fragments the biggest of which is the Sao Francisco craton. Both these formations appear to have a shared history from 3.0 to 1.7 Ga, indicative of a common border throughout that period (Cordani, 1999). However, the Middle and Late Proterozoic saw the northwestern mass remain undamaged by tectonic and orogenic activity, while the southeastern formation was broken up (Cordani, 1999). By the beginning of the Brasiliano orogeny in the Late Proterozoic, 98% of the crust known to South America today had been formed (Cordani, 1999). The Brasiliano cycle brought the final changes to the structure of the South American Platform’s basement. The Platform was part of successive supercontinents until the early Phanerozoic, when it broke off from Western Gondwana (Almeida, 2000). The Brasiliano structures are the main source of sedimentary cover across South America (Almeida, 2000).

(Cordani, 1999)

The Andean Cordillera

Stretching 8000 km along the western coast of South America (yellow in the figure above), the Andean mountain range rose from the interactions of the Nazca plate with the South American plate. These interactions include convergence with oceanic terranes during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic (Northern Andes), subduction and volcanic arc activity (Central Andes), and the closing of a back-arc oceanic basin (Southern Andes) (Ramos, 1999).

REFERENCES CITED

Almeida, Fernando Flávio Marques de, Benjamim Bley de Brito Neves, and Celso Dal Ré Carneiro. "The origin and evolution of the South American Platform." Earth-Science Reviews 50, no. 1 (2000): 77-111.

Cordani, Umberto G., and Kei Sato. "Crustal evolution of the South American Platform, based on Nd isotopic systematics on granitoid rocks." Episodes 22 (1999): 167-173.

Davis, D. W., and J. B. Paces. "Time resolution of geologic events on the Keweenaw Peninsula and implications for development of the Midcontinent Rift system." Earth and Planetary Science Letters 97, no. 1 (1990): 54-64.

Hoffman, Paul F. "United Plates of America, the birth of a craton-Early Proterozoic assembly and growth of Laurentia." Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 16 (1988): 543-603.

Ramos, Victor. "Plate tectonic setting of the Andean Cordillera." Episodes 22 (1999): 183-190.

The Hateful Dead. “Plate Tectonics The Evolution of North America” Online video clip. Youtube. Youtube. 2008. Web. 30 Jan. 2014

Van Schmus, W. R., and W. J. Hinze. "The midcontinent rift system." Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 13 (1985): 345.

Vidotti, R. M., J. B. Curto, R. A. Fuck, E. L. Dantas, H. L. Roig, and T. Almeida. "Magnetic expression of the Transbrasiliano Lineament, Brazil." InAGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, vol. 1, p. 0986. 2011.

Wicander, Reed, and James S. Monroe. Historical Geology. Toronto: Brooks/Cole, 2004.

Cordani, Umberto G., and Kei Sato. "Crustal evolution of the South American Platform, based on Nd isotopic systematics on granitoid rocks." Episodes 22 (1999): 167-173.

Davis, D. W., and J. B. Paces. "Time resolution of geologic events on the Keweenaw Peninsula and implications for development of the Midcontinent Rift system." Earth and Planetary Science Letters 97, no. 1 (1990): 54-64.

Hoffman, Paul F. "United Plates of America, the birth of a craton-Early Proterozoic assembly and growth of Laurentia." Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 16 (1988): 543-603.

Ramos, Victor. "Plate tectonic setting of the Andean Cordillera." Episodes 22 (1999): 183-190.

The Hateful Dead. “Plate Tectonics The Evolution of North America” Online video clip. Youtube. Youtube. 2008. Web. 30 Jan. 2014

Van Schmus, W. R., and W. J. Hinze. "The midcontinent rift system." Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 13 (1985): 345.

Vidotti, R. M., J. B. Curto, R. A. Fuck, E. L. Dantas, H. L. Roig, and T. Almeida. "Magnetic expression of the Transbrasiliano Lineament, Brazil." InAGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, vol. 1, p. 0986. 2011.

Wicander, Reed, and James S. Monroe. Historical Geology. Toronto: Brooks/Cole, 2004.